Micron-Level Ceramic Injection Molding and the Science Behind Its Precision

Ceramic injection molding (CIM) is one of those manufacturing methods that sounds straightforward until you look closely. You start with ceramic powder, you shape it in a mold, then you heat it until it becomes a dense, hard ceramic part. Simple, right. The real magic is that CIM can produce intricate components with features so small and consistent that they feel almost impossible for a material as unforgiving as ceramic, and that’s where the technology behind ceramic injection molding really earns its reputation. That micron-level precision does not come from one “special” step. It comes from a chain of tightly controlled science and engineering choices that make the final result predictable.

Why precision is a bigger challenge with ceramics than most materials

Ceramics behave differently from metals and plastics, and that difference matters when you are chasing tight tolerances.

Ceramics do not bend, they punish mistakes

A metal part can sometimes tolerate slight distortion. A polymer part can flex. A ceramic part, once fully densified, tends to be rigid and brittle. That means tiny defects that would be cosmetic in another material can become functional failures in ceramic. Precision is not only about looking good, it is about survival under real-world stress, heat, or wear.

The part changes shape more than once

In CIM, the molded shape is not the final shape. The part starts as a soft, binder-rich body, then loses binder, then shrinks during densification. Each transition is a chance for distortion. Micron-level accuracy is really the art of managing change without losing control.

Fun fact two ceramic parts can look identical after molding, yet end up measurably different after firing if their internal powder packing is not consistent.

The feedstock is engineered to behave like it belongs in a mold

Precision starts before the mold even closes.

Powder packing is the first “measurement”

CIM uses fine ceramic powder mixed with binders to create a moldable feedstock. The powder is not just “ceramic dust.” Its particle size distribution, surface chemistry, and shape affect how it packs together and how it flows. If packing is uneven, the part can shrink unevenly later, which is a precision killer.

The binder system is a temporary superpower

The binder is what lets the ceramic mixture flow through runners, gates, and into tiny features. A good binder system does three things at once:

- It carries powder smoothly without separating.

- It fills small details without trapping voids.

- It holds the molded shape firmly enough to survive handling.

Because the binder later disappears, it has to perform perfectly and then exit politely without damaging the structure.

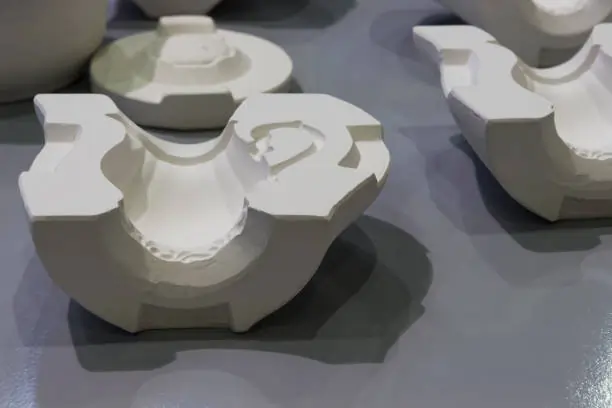

Mold design is a science experiment disguised as tooling

In CIM, the mold is more than a shape. It is a controlled environment for flow.

Gating, venting, and flow direction shape the final outcome

The location of the gate and how the material enters the cavity determine how the feedstock flows and where weld lines form. Air management matters too, because trapped air can create micro-voids or surface defects. Even if those defects are not visible, they can influence strength and dimensional stability after firing.

The mold must predict the future

Because the part shrinks during sintering, the mold is made “oversized” in a deliberate way. This is not guesswork. It is based on known shrinkage behavior of the feedstock and the process window. The better the data and process control, the more confidently the tooling can be designed to land on target dimensions.

Fun fact molds for CIM are often designed with the mindset of “designing for shrinkage” rather than “designing for shape,” which flips the usual intuition most people have about molding.

Injection parameters turn good tooling into repeatable results

Even with great feedstock and tooling, poor settings can ruin accuracy.

Temperature controls flow, pressure controls fill

If the feedstock is too cool, it resists flow and may not fill thin sections properly. If it is too hot, it can separate or behave inconsistently. Pressure and speed influence how fully the cavity fills and whether internal stresses form. These stresses can later reveal themselves during debinding or sintering as warpage or dimensional drift.

Repeatability is built shot by shot

Micron-level precision relies on maintaining consistent conditions. That includes not only melt temperature and injection speed, but also mold temperature, cooling behavior, and cycle timing. The goal is to make every “green” part start life as similarly as possible, so it behaves predictably later.

Debinding is where patience protects precision

Once the part is molded, it is still mostly binder by volume. Removing that binder is delicate.

Binder removal must be controlled, not rushed

Debinding is typically done using thermal, solvent, catalytic methods, or combinations depending on the binder system. The challenge is that binder needs to leave without leaving cracks, void pathways, or internal stresses behind. If debinding happens too fast, internal pressure can build and damage the part. If it is uneven, it can create density gradients that show up later as distortion.

Sintering is controlled shrinkage, not a random outcome

Sintering is the step that turns the fragile body into a dense ceramic. It is also where most dimensional change happens.

Shrinkage becomes predictable when density is consistent

During sintering, particles bond and the part shrinks as pores close. If the molded body had consistent powder distribution, shrinkage will be uniform. If not, different regions shrink differently, and that is how you get warpage. The science of CIM is about making the internal structure consistent enough that shrinkage behaves like math, not luck.

Fun fact sintering can be thought of as “locking in” the part’s microstructure, and the microstructure often determines wear resistance and strength as much as the part’s outer shape.

How the last few microns are actually achieved

CIM often produces near net-shape parts, but final precision depends on how the process is finished and verified.

Measurement closes the loop

Dimensional inspection is not an afterthought. It feeds back into process tuning, mold compensation decisions, and quality control limits. The tighter the tolerance required, the more carefully measurement strategy is integrated with production.

Finishing is used strategically, not as a crutch

When needed, selective grinding or polishing can refine critical surfaces. The advantage of CIM is that finishing is targeted, not extensive. You are not machining a whole part from a solid block. You are perfecting an already precise geometry.

Ceramic injection molding achieves micron-level precision by treating every step as part of one system. The feedstock is engineered for stability and flow. The mold is designed to guide material behavior and predict shrinkage. Injection settings are controlled for repeatability. Debinding is managed gently to protect structure. Sintering is tuned so shrinkage is uniform and expected. When all of that clicks, CIM stops feeling like an ordinary process and starts looking like controlled physics, repeated thousands of times with the same outcome.

What Professional Maids Won’t Clean and the Smart Reasons Behind It – SizeCrafter

Why Professional Chefs Keep Reaching for Small Batch Stoneware on the Pass – SizeCrafter